How do learners make use of foreign language learning materials? This was the question that I set out to answer in my ph.d. thesis. Along the way, I learned to use to methods for evaluating usability of a product (think-aloud protocols and constructive interaction), learned how to analyze the results quantitatively (which was scary), and found new ways to look at the data qualitatively (conversation analysis). Especially through detailed qualitative analyses of how our study participants made use of the learning materials in our usability test settings, I learned more about the sequential organization of such sessions, how instructions are realized, and how different visual and other aspects of the learning material drafts were made relevant.

In this blog post, I’ll therefore focus on insights from the qualitative analyses of one study.

Okay, let’s start with a crazy exercise: Imagine you’re an advanced student of German (I know this may be hard, but stay with me). Your vocabulary is extensive enough to engage in a large variety of discourses and your grammar is more than acceptable as well. One thing that bothers you, however, is that people still easily identify you as non-native speaker albeit your impressive vocabulary and grammar skills. Now, one thing you could work with is isolated pronunciation exercises to learn how to pronounce different words more ‘native-speaker like’ (whatever that means). Alternatively, you could take a step back and take a look at larger units on utterance level and work with those.

In simple terms, this was our research group’s point of departure for a study to figure out ways to help students of German learn to use prosodic features such as intonation and stress consciously and meaningfully. Previous research on the role of prosody (i.e. intonation, stress, rhythm, etc) in interaction has shown that appropriate use of prosody is essential in order to “precisely deliver the intention of the speaker and to effectively communicate with the native speakers in the actual speaking situation” (In & Han, 2015: 48) and to avoid cross-cultural misunderstandings caused by intonation features (Clennell, 1997; Gumperz, Jupp, & Roberts, 1979). Nonetheless, prosodic features are hard to pinpoint, explain, and practice and are therefore rarely a part of the foreign language learning syllabus and thereby remain largely unattended to by learners and teachers. In order to explore ways to help learners and teachers to incorporate exercises on intonation and other prosodic aspects into language learning, we set out to develop learning materials.

Typically, new learning materials are not systematically evaluated for their usefulness and usability prior to publishing which often leads to laborious and costly revisions. If materials are tested at all, they are evaluated by experts on the respective topic and teachers. Learners are rarely included in the process.

In our project, we wanted to include learners in the development and evaluation process and thus decided to test our first drafts of materials with potential learners. Regarding learning material on German prosody, we decided to conduct so-called constructive interaction sessions (Miyake, 1982; O’Malley, Draper, & Riley, 1984) in which two study participants at a time try to figure out the material together. We videotaped these sessions and analyzed them afterwards.

Let’s go back to our “Imagine you were…” exercise. Now, you’re not just any advanced learner of German; you and your pal Ginny have been recruited to participate in our study. So the two of you show up, are instructed by a researcher and are then left to your own devices to figure out how to use the learning materials that the researcher gave you before she left the room.

Here’s a picture of you while you are working:

The (translated) transcript documents a sequence in which you work with the first of six material drafts (cf. green box in the picture). This is the very beginning of your session, and while you start practicing how to pronounce the target sentences (“Messer und Gabel liegen neben dem Teller”, “Ob ich Süßigkeiten kaufen darf”), you and your co-participant also have to figure out how to organize this whole endeavor. The instructions given by the researcher give you a brief outline of some milestones you should reach (e.g. “practice the pronunciation of the sentences”, “when you feel like you’ve figured them out, produce them once ‘for the record’” […], “repeat with the next set of materials”), but how you get from one milestone to another is up to you.

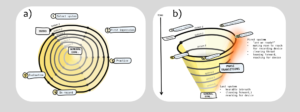

This was one of the things I focused on in my thesis: The interactional organization of a constructive interaction session. Analyzing in detail the nine sessions that we had recorded, I found and described the recurring structure, or, phases, that all groups of participants went through (see image, a)). In the course of the session, transitions between these phases became increasingly routinized and minimalistic. In other words, while the participants initially put a lot of interactional work in form of words and gestures into moving from one phase of the session into another, this negotiation requires less and less work over time as the participants need less cues to recognize that their co-participant is ready to move on (see image, b)).

So, what did I learn from looking at and describing in detail how advanced learners of German make sense of learning materials on German prosody in a usability test setting? First of all, looking at how you and the other participants in the study acted out the instructions we had given gave me a more nuanced view of what a usability test session actually is. While descriptions of and guides to usability testing describe usability testing as a context in which study participants ‘open their minds’ and ‘verbalize their thoughts’, the things that are actually going on are much more varied, localized and context-bound. Secondly, using more than the conventional methods of checklists and performance-focused learning material evaluation added new insights to the evaluation of learning material drafts in general. Finally, through user-centered methods to collect and analyze data from a potential learner’s point of view, I learned more about how the usability test framework affords some behaviors and inhibits others that can be used to evaluate the materials from a usability perspective.

In my thesis, I used these insights to make a number of concrete suggestions for future redesigns of the tested materials. I suggested redesigns based on the material drafts we had made as well as more general suggestions on possible ways to design a complete set of materials focusing on German prosody informed by not only the participants’ comments but also the way they used e.g. embodiment in what I’ve referred to as practicing phases.

So in this way, the detailed qualitative analyses of how our study participants made use of the learning materials in our usability test settings yielded descriptions of the sequential organization of such sessions, how instructions are realized, and how different visual and other aspects of the learning material drafts were made relevant.

Nathalie Schümchen is currently an external lecturer at SDU teaching subjects within linguistics. Parts of this article are based on her PhD thesis which she completed in December 2019 (see Schümchen, 2019). She is interested in all aspects of social interaction, especially from a micro-analytical perspective (She is also currently looking for a job ?).

Read more:

Clennell, C. (1997). Raising the pedagogic status of discourse intonation teaching. ELT Journal, 51(2), 117-125.

Gumperz, J. J., Jupp, T. C., & Roberts, C. (1979). Crosstalk: A study of cross-cultural communication. London: National Centre for Industrial Language Training in association with the B.B.C.

In, J., & Han, J. (2015). The prosodic conditions in robot’s TTS for children as beginners in english learning. Indian journal of science and technology, 8(s5), 48-51. doi:10.17485/ijst/2015/v8iS5/61476

Miyake, N. (1982). Constructive Interaction. Retrieved from

O’Malley, C., Draper, S., & Riley, M. (1984). Constructive interaction: a method for studying user-computer-user interaction. Paper presented at the IFIP INTERACT’84 First International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

Schümchen, N. (2019). How do learners make use of foreign language learning materials?: a micro-analytical study to support the evaluation and development of visual learning instructions. (Dissertation/Thesis Monograph), University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/v2bmc7p