July 2022 saw the approval of a new research unit at Aarhus University – the Centre of Voice Studies. Why a centre of voice studies? Why now? And who’s behind it?

First, some note on the voice. The vast majority of human beings communicate with the use of sounds coming out of their bodies. Sounds produced by the vocal tract are particularly relevant. But sounds are far from limited to human communication. Vocal variation is everywhere around us, whether we communicate with human or non-human animals.

There is no doubt that the voice provides interlocutors with a plethora of meaningful information. This information is linked to our bodies as well as our cultures. Just from a single word, the hearer often infers information linked to biological age, biological sex, social gender, health, and the emotional state and even disposition of the speaker. But this is not where vocal variation ends in terms of its communicative potential: regional affiliation, ethnic background, sexual orientation, vocal attractiveness, morality, whether we agree or disagree, can all be coded in the mosaic of our voices. And there is still more that the voice does for most of us.

The voice has been so important in human communication that endless songs and poems focusing on the topic seem to have been produced. See e.g.:

- “Voices” by Madonna

- “Your voice is my favourite sound” by Dat Boy Lucky

- “Love your voice” by JONY.

- The band titled “Voices Carry”

- “Voices in the sky” by The Moody Blues

- “Still within the sound of my voice” by Glen Campbell

- “Hear my voice” by Celeste

- “Use my voice” by Evanescence

And these came out of a very superficial internet search!

Indeed, the voice is so fundamental to who we are that it has been frequently used metaphorically as well, as also apparent from the song titles above. Phrases come to mind such as “to give the voice to the voiceless” or “find your voice”.

And let’s not forget about globally known examples which would lead us, the audience, to think of the voice almost as a magical “organ”, as in the case of Disney’s Ariel in The Little Mermaid, where Ariel trades her voice for the opportunity to get closer to her object of affection.

But how do we define the voice exactly? Across disciplines, researchers have used a very wide range of both figurative and non-figurative meanings of the word. Even within a single discipline, it is not at all unusual to come across rather different definitions, and it can therefore be quite common to find an absence of consensus on how to analyse vocal variation. This is one of the main motivations for the existence of the Centre of Voice Studies at Aarhus University.

Although Míša Hejná, the founder and the current director of the centre, identifies primarily as a linguist, the centre aims to provide a network for those who are interested in interdisciplinary approaches to the voice. We may all have our disciplinary homes, but we aim to learn from our visits to each other’s disciplinary abodes. How do others tackle vocal variation and why? What sorts of questions are they interested in, and why not other questions? How do they apply their knowledge of vocal variation?

Since the founding of the centre, our cross-disciplinary representation has grown with 30 members as of time of writing, associated with 13 institutions and 9 countries. The disciplines of our members embrace aesthetics, cultural studies, film studies, information studies, linguistics, literature, media studies, musicology, psychology, and speech and language therapy (in alphabetical order). Right now, the members are primarily researchers, but we’re very happy to also have a couple of practitioners in our midst. We’ve expanded since our humble beginning of the five researchers based at the Department of English at Aarhus University brought together by a Carlsberg-funded project titled “‘It’s not what you said, it’s how you said it’: an empirical approach to human voice as the outward expression of inner character” (Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, Mark Eaton, Mathias Clasen, Míša Hejná, Zac Boyd – the five voiceketeers!). But where do we go in the years to come? Funded projects don’t last for ever…

We will continue hosting approximately 6 zoom talks per year, as we have done over the past year. While many of us might be feeling rather over-zoomed after the pandemic, this is nevertheless the most accessible way for the members of the centre to meet. If we want to get exposed to a wide range of interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary perspectives, the centre needs to be open across national borders. Some of our members have in addition expressed the sentiment of feeling somewhat stranded and isolated at their home institutions, and being able to zoom in to discuss vocal variation with kindred spirits is seen as a bit of a treat (or so I’m told by some of the soulds in question).

The centre officially opened on the 16th of August 2023. In the spirit of intended inclusiveness and interdisciplinarity, throat teas and honey were provided for the attendees, who could read poetry about the voice on the walls and participate in perceptual experiments linked to which voices sound attractive (Why not help us figure out which voices are attractive and why?) and which voices sound evil and immoral (Why not evaluate the voices of Dungeons and Dragons here?). We were also extremely pleased that Sarah Mann and Ella Luhtasaari could kick things off with their musical recital, which demonstrated to the audience the awesome potential of the singing voice to move people emotionally.

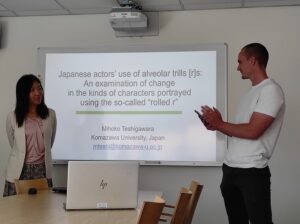

The opening was followed up by our conference, which included disciplines such as aesthetics, media studies, musicology, linguistics, and various combinations of these. We enjoyed talks on topics ranging from voices in popular culture to voices in social-psychiatric interactions, with lively and rigorous presentations on research on voice studies. We ended on some notes that took us to the edge of humanity, with voices of Artificial Intelligence. Indeed, we aimed to go boldly and explore both more and less conventional areas.

Open Access proceedings are being cooked as I write (in collaboration with Oliver Niebuhr, and we hope to hold this weirdly but wonderfully interdisciplinary endeavour alive in the years to come, with quadrennial instalments.

We’ll see where the future leads us… Hopefully somewhere good! Although there is no doubt that vocal variation plays an extremely important role in our life, there are still many gaps in our knowledge. The centre aims to help to encourage even more interdisciplinary research to help to tackle some of these.

And if you’d like to join us, just let us know (humanvoice2023@cc.au.dk or misa.hejna@cc.au.dk).

Acknowledgement: I am very grateful to Mathias Clasen for his numerous comments on an earlier version of this Lingoblog contribution.

Logo of the Centre of Voice Studies at AU, designed by Zac Boyd (https://www.zacboyd.co.uk/).

Míša Hejná is an Associate Professor in the English Language at the Department of English at Aarhus University, Denmark. She is the founder and the current coordinator of the Centre of Voice Studies at AU. She works in the areas of phonetics, sociolinguistics, and interdisciplinary studies.