”Now that I am dating an Italian, I will have to start learning Italian”… “I am going to Portugal during my summer vacation, can I borrow your dictionary?” … In Europe we are used to countries having each their language – Denmark has Danish, Sweden has Swedish, Germany has German and so on. But this is a truth with modifications. First of all, countries can contain more than one language, either minority languages such as German in Southern Jutland and Danish in the Flensburg area, or like entire language areas such as Greenlandic and Faroese in Denmark or Sorbian in Germany. Not to mention countries like India or China, which each contain hundreds of languages. Second, several countries can “share” a language, as is the case for instance in Germany, Austria and Switzerland with German or Great Britain, the US, Canada and Australia with English. Furthermore, it can be difficult at times to determine whether a language border is politically motivated, like the one between Croatian and Serbian, where people in the country formerly known as Yugoslavia spoke ‘Serbo-Croatian’. And who knows if ‘Bokmål’ and New Norwegian would have been promoted to independent languages without the independence of Norway from Denmark.

Some languages, for instance Kurdish in Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Iran, are so unfortunate that their territory is spread over several countries without being “in power” in any of them. But do languages without a country and territory even exist? Yes, in fact, they do. This happens if a language survives its speakers or if its speakers spread due to systematic persecution. You can say that the first scenario is the case with Latin, which survived the Roman Empire as the language used in church and schooling. Examples of the second scenario are Romani, spoken by the Sinti and the Roma, or Jiddish, spoken by some Jews. In some cases, the persecution did not lead to a complete dissolution of the territory of a language, but still to a spread of the survivors to the whole world, which is the case for Armenian. Such a language community without a territory is called a diaspora and will typically have retained many common cultural features in addition to the language, for instance food, music or family patterns.

Then there is the outsider – the language which is completely based on a diaspora community and has never had a territory of its own, let alone a country: The international language Esperanto. Esperanto is an artificial language developed specifically to be for no one and everyone – a language designed to be easy to learn and enable contacts and friendships across borders and cultural differences. The last part constitutes the spice in Esperanto – it opens doors to other cultures or quite literally to the homes of kind-hearted Esperantists in a country where many would otherwise have been referred to an anonymous hotel room as well as frustrating struggles with the broken English of the native community. Esperanto was born in the same period of time – the 1880s to 1890s – where many of the revolutions of the following century were just beginning: Socialism, communism, Darwinism, atheism, Zionism, modernism, women’s voting rights, the automobile, train tracks, electricity, the phone and so forth. And the new world language was truly revolutionary. The world’s dictators did not like that their subjects were to have first-hand access to the world outside. And so Esperantists were naturally persecuted and sent to prison camps by Hitler, Stalin and Franco alike.

Today, the language profits because it is much easier for a diaspora community to keep in contact with each other. The internet, Facebook, and Ryan Air make it easy to find and meet foreign friends. One can learn Esperanto online (eg. lernu.net) or with an app (eg. Duolingo), and in a time with no pandemic one can find many international Esperanto events where participants speak Esperanto while being on vacation, on a hike, at a party or while discussing political topics and all sorts of other alternative ideas. The target group can be young people, professionals, families or people who just want to meet others. These meetings, spanning the whole year, are what constitutes the ”territory” of Esperanto. This territory is decentralized and asyncronous, but it is there. As such, I, the blogger, speak Esperanto as my main language a few weeks a year in connection with travel or projects with the European Union, and while I was a student I sometimes spoke Esperanto a few months a year.

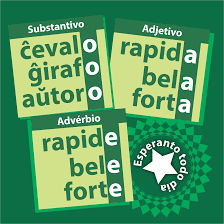

These days Esperanto stands on one of two legs so to speak, one linguistic and one ideological. The linguistic distinctiveness of Esperanto is due to the fact that it is regular and modular in construction, and everything is written as it is spoken. If one has learned a few hundred words, it is possible to understand and create thousands of other words, and with a thousand word stems one is in a better position than if one had learned one of the languages normally taught in school, especially if this language is not close to one’s native language. As an example, school experiments have shown that Esperanto is 15 times easier to learn for German speakers than French, measured by vocabulary and fluency. The vocabulary is, by the way, not invented without rules, but has many Latin roots in particular and has a sound system based on Italian. As an English speaker, one can recognize ’sana’ (healthy) from words like sanitary. Words with the opposite meaning are created with a regular rule, putting in ‘mal-‘ as a prefix: ‘mal/sana’ (sick) even though you do not say ‘unsick’ in English. Esperanto has 40-50 of these affixes in total, including (‘fi-‘ and ‘-aĉ’) to create derogatory and swear words. Some affixes cover semantic categories, for instance people (’-ul’), places (‘-ej’) and tools (‘-il’), so that hospital becomes ‘mal/san/ul/ejo’. Ambiguity disappears as well in Esperanto. When one wants to say ‘healthy’ in the sense ’health-promoting’ (eg. healthy food), Esperanto has a suffix, ‘-ig’, which means ‘-making’, creating ‘san/iga’. Guess how to say sickness-inducing! … Yes, ‘mal/san/iga’.

Another advantage is that grammatical categories – such as word classes, tense and number – are unambiguously marked. The Danish ‘lærer’ (to learn/to teach/teacher) is either ‘instru/as’ (teach) eller ‘instru/ist/o’ (teacher). In this case ‘-as’ is a present tense marker, ‘-ist’ is a suffix of profession and the ‘-o’ suffix for nouns in singular number, while ‘-a’ in ‘san/a’ marks an adjective. The plural suffix is always ‘-j’, so that ‘sick teachers’ becomes ‘mal/san/a/j instru/ist/o/j’.

Try filling out the following table (and if it is too easy, then try with German for instance)

| Sheep | Ewe | Lamb | Sheepfold | |

| Ŝafo | Virŝafo | Ŝafido | ||

| Dog | Male dog | Puppy | Dog house | |

| Hundo | Hundino | Virhundo | Hundejo | |

| Horse | Mare | Stallion | Horsefold | |

| Ĉevalo | Virĉevalo | Ĉevalido | ||

| Cow | Cow | Bull | Calf | Cowshed |

| Bovo | Bovino | Bovejo | ||

| Pig | Pigsty | |||

| Porko | Porkino | Virporko | Porkejo | |

| Hen | Rooster | Chicken | ||

| Koko | Kokino | Kokejo |

And where is the logic in Danish when whales and rhinoceros have calves, but foxes have puppies?

Sometimes one is met with the presumption that an artificial language, because it is logical in structure, necessarily has to be “emotionally cold” and cannot function as a vehicle for original culture. The history of Esperanto shows this to be false. The language has worked as a cultural crucible med cross inspiration between cultures and has created both original literature, theatre, and music. If one wants to poetically portray the flight of an eagle over a mountain landscape and uses the word ‘mal/monto’, the mind of the reader has to first create the picture of a mountain (‘monto’) and then turn it into its opposite (‘mal-‘). The gorge the eagle soars over becomes much deeper and steeper than would one have used the normal word ‘valo’ (valley). This kind of flexibility makes it much easier to translate to Esperanto than from it – ‘unmountain’ just doesn’t work in English. And the everyday language creates new words all the time in a creative fashion, exactly like other languages, by having speakers invent then as the world changes. Examples include ‘komputilo’ (“calculator tool”) and ‘poŝtelefono’ (”pocket phone”). And when there are several options, regular use often wins over the suggestion from the Esperanto academy. Since Esperanto is the only artificial language with a certain number of native speakers, linguists have been able to observe this creativity from day one so to speak. Children with Esperanto as their native tongue, typically with parents from different countries living in a third country, often hear Esperanto at home and other languages from uncles, aunts, grandparents, and in kindergarden. This makes them highly stimulated with languages and have lots of linguistic creativity. They get a quick start with Esperanto in particular – every time their little brains “get” a category, for instance plural, past tense, perfect tense, or a rule about creating words, like the ‘mal-‘ prefix or the ‘-is’ past tense marker, it works every time, and the new rule can be applied to all their known words. This is opposed to children of natural languages, who will be corrected if they say ‘goed’ instead og ‘went’ or never really figure out the difference between ‘lay’ and ‘lie’.

Apart from being a creative and easily accessible language, Esperanto has another interesting aspect as well – the so-called “inner idea” (interna ideo). In essense, this means that the people who take their time learning Esperanto usually are open to and curious about other people and cultures. In the beginning, Esperanto importantly a peace project in a torn Europe, where language was a class divide and a tool for power. Today the “inner idea” shows itself by having an Esperanto community which contains an overrepresentation of pacifists, vegetarians, anarchists, eco-freaks, climate cuckoos and nerds from around the world. In the good sense.

People often ask me how many people speak Esperanto today. The answer is that if you look at the Esperanto community, the “diaspora”, there are as many today as there were yesterday and will be tomorrow, since it is not a political party to vote for, but a “people” you are part of. My guess is that there are about 100,000 people who speak Esperanto freely and native tongue-like and use it socially or culturally. This places the language in between Faroese and Icelandic in terms of speakers, with an equal interest from these 100,000 people to meet each other as would be the case for Icelandic speakers if a vulcanic eruption were to spread them across the world. Other counts exist, though they measure other features – for instance, you could count millions if you were to count based on the number of textbooks sold overall, and currently there are a couple of millions who have learned a little or much Esperanto on Duolingo.

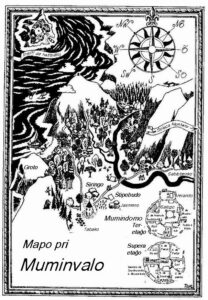

But let us get back to the point of departure – the language without a country. In Esperanto when one talks about ‘Esperantujo’ or ‘Esperantio’ (a la ‘Germanujo’/’Germanio’, ‘Danujo’/’Danio’), it is not a reference to a state or region, but the entirety of Esperanto’s cultural niches, the international events, and what we here have called diaspora. But curiously there are still a few real places that make up small suggestions for a geographical “Esperantujo” or have tried to be. For instance, in the early days of Esperanto there was an area (Moresnet) in the no-man’s-land between Belgium and Germany that had many speakers of Esperanto and tried to become a politically neutral territory (Neŭtrala Moresnet). That dream was crushed, however, with the beginning of World War 1, where Moresnet was first annexed by Prussia and after the war it was given to Belgium, now a German-speaking enclave, Kelmis. Other failed declarations of independence with Esperanto as the official language include the “Rose Island” (Insulo de la Rozoj) in the Adriatic Sea and the micro republic of Molossia in Nevada.

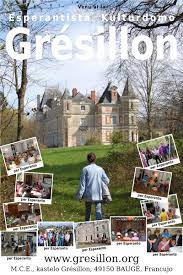

A true ‘inner idea’ example of an “Esperantujo” today is Bona Espero, a small community with international support in the Brazilian federal state of Goiás who perform social work for the locals and run a school for orphans – with Esperanto as a second language besides Portuguese. Another example is Kastelo Grésillon, a real Loire castle with an endless number of rooms, used as a cultural center and for Esperanto courses driven by a large group of passionate Frenchmen who own micro shares in the project. I have once experienced this place as a set for a French-German youth congress, and I have been there for a workshop about language didactics. I was to show how to use games, play and drama in language education, but there was also a course in the Czeh method – a technique especially developed for Esperanto teachers, where you only use things, signs, flashcards, and the language itself because the teachers are to teach people with mixed linguistic backgrounds and thus cannot explain anything using another language because the students do not have a language in common. Yet.

I have personally contributed to creating a small Esperantujo oasis once when we as students rented a big house in the German capital and declared it an Esperanto commune. Among other things we were part of the overnight service Pasporta Servo and hosted, on average, two Esperanto speakers traveling through the area every day. But the most exotic piece of Esperantujo I have experienced was Krucio – a mini village by the sea in the Mexican desert in Baja California, 500 kilometers from the nearest town and 15 kilometers from the nearest road.

The few people there were on the farm all spoke Esperanto and received money from the Mexican government for experimenting with desert agriculture and alternate building materials. You could fish and supplies were shipped to the farm once a month, and all water had to be produced on site through distillation, both for plants and humans. That kind of work takes idealism.

The language without a nation is by no means a language without a people. Esperanto attracts idealists and makes strangers friends. When everyone is different, no one is different, and everyone is just (interesting) people. Language creates understanding, and Esperanto is the only language in the world that has a word (‘krokodili’) for leaving others out by speaking a language they do not understand.

Dr. Phil. Eckhard Bick is a research lecturer at the University of Southern Denmark and works with computational linguistics and language technology for a number of languages, one of these being Esperanto. He has for instance developed programs for spelling- and grammar errors in Danish and Esperanto as well as comma control programs for English and German. Eckhard Bick has published research articles on a variety of subjects but has also written a textbook about Esperanto for students, translated the Moomin Valley books into Esperanto and published Esperanto dictionaries. What may be his greatest Esperanto project is a program that continuously translates the entire English Wikipedia into Esperanto (Wikitrans) and integrates it with the original Esperanto Wikipedia. On behalf of the university, he has worked on two European Union projects concerning Esperanto, lingvo.info (a website about the languages of Europe) and Multilingual Accelerator (a school project with Esperanto as a propaedeutic language).

mirinda artikolo!

amike

renato

tre bona artikolo!

amike

renato

Now I’ve read this article twice (once in English, and once in Danish) and thought it over all morning. Here’s my thoughts on it.

I was able to fill in the missing words in Danish (my first language), in English and mostly in German without resorting to a dictionary – even to the extent of missing some cells for “grown to size, but not yet sexually mature”, for “small one male” and “small one female”, and finally for “castrated male” specimen of many of the animals.

Of course I could fill in the blanks in Esperanto as well.

But, and for me there’s a big but. Filling out the missing words in Danish, English and German left me with a sense of accomplishment, while the Esperanto did not. It was like solving a crossword as opposed to solving a Sudoku.

For me the learning of any language is a travel into the language, a learning of all the quirks, connotations and double entendres of said language. A trip through the etymological sludge and dregs. And as you hinted, learning a new language is also learning a new way of thinking, a new culture, new pathways in the brain.

For me the non-regularity of a language is an advantage, a spice, a thing to be savoured, not the opposite (which is not an un-advantage but a drawback. I had to look this up).

I would also like to know more of the children brought up with Esperanto as their first language. What happens when they grow up? Do they feel cheated out of a mother-tongue like the child brought up with Klingon, or do they feel that they are given something extra? And what about the not-so-gifted or intelligent children who are not able to fully learn more than one language, how do they function in a not Esperanto speaking world?

I sympathise with the learning of Esperanto, but I feel an indirect slight at people who are not Esperantists in this article, which is only natural for a small, partisan community, but not in its place in a linguistic setting.

And in this sentence: “This is opposed to children of natural languages, who will be corrected if they say ‘goed’ instead of ‘went’ or never really figure out the difference between ‘lay’ and ‘lie’.” I think you are comparing pears and coconuts. The people speaking Esperanto are all what I call linguistically aware, that is to say they know more languages, they care about languages, and they generally taken know what’s correct or not. You won’t have a true comparison between Esperanto speakers and natural language speakers until you have people speaking Esperanto as their sole language, having learnt from their parents, who also only speaks this in common, and maybe even badly. Like the Danish people saying “Jeg fik det afvide” and when told that it is incorrect says: “So what, you understand what I mean!”. Until you have people like these, the linguistically unawares speaking Esperanto as well, you cannot compare children’s language skills.