Today it is Hebrew Language Day. It is each year on 21 tevet, which is Eliezer Ben Yehuda‘s birthday. For that occasion, Ghil’ad Zuckermann displays his view on the underlying roots of the Israeli language.

First, a little background information:

Background on the Hebrew language

Hebrew was spoken after the so-called conquest of Canaan (c. thirteenth century BC). Following a gradual decline (even Jesus, ‘King of the Jews’, was a native speaker of Aramaic rather than Hebrew), it ceased to be spoken by the second century AD. The Bar-Kokhba Revolt against the Romans in Judaea in AD 132-5 marks the symbolic end of the period of spoken Hebrew. For more than 1700 years thereafter, Hebrew was comatose, a sleeping beauty. It served as a liturgical and literary language, and occasionally a lingua franca for Jews of the Diaspora, but not as a mother tongue.

What language is Israeli?

The formation of the revival language known as ‘Israeli Hebrew’ (henceforth Israeli) was facilitated at the end of the nineteenth century by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (1858-1922, the most famous Hebrew revivalist), school teachers, authors, and other intellectuals to further the Zionist cause. Earlier, during the Haskalah (enlightenment) period of the 1770s-1880s, writers such as Méndele Móykher-Sfórim (originally Shalom Abramowitsch) produced works and neologisms which eventually contributed to Israeli. However, it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that the language was first spoken.

During the past century, Israeli has become the official language of Israel, acting as the primary mode of communication throughout all state and local institutions and in all domains of public and private life. Yet, with the growing diversification of Israeli society, it has come also to highlight the very absence of a unitary civic culture among citizens, who, unfortunately, seem increasingly to share only their language.

Israeli is currently the only de jure official language of the State of Israel (established in 1948), with Arabic being recognized as having a special status and with English as a de facto in langscape (linguistic landscape) but not a de jure official language. Israeli is spoken to varying degrees of fluency by 9.3 million Israeli citizens; it is a mother tongue for most Israeli Jews (whose total number is almost 7 million), and a second language for Israeli Muslims (Arabic-speakers), Christians (e.g. Russian and Arabic-speakers), Druze (Arabic-speakers), among others.

The Survival of Yiddish beneath Israeli

By Professor Ghil‘ad Zuckermann

Just before the end of the second millennium, Ezer Weizman, then President of Israel, visited the University of Cambridge to familiarize himself with the famous collection of medieval Jewish notes known as the Cairo Genizah. President Weizman was introduced to the Regius Professor of Hebrew, who had been allegedly nominated by the Queen of England herself.

Hearing “Hebrew”, the president, who was known as a sákhbak (friendly “bro”), clapped the professor on the shoulder and asked: מה נשמע má nishmà, the common Israeli “What’s up?” greeting, which some take to literally mean “what shall we hear?”, but which is, in fact, a calque (loan translation) of the Yiddish phrase וואָס הערט זיך vos hért zikh, usually pronounced vsértsəkh and literally meaning “what’s heard?”

To Weizman’s astonishment, the distinguished Hebrew professor hadn’t got the faintest clue whatsoever about what the president ‘wanted from his life’. As an expert of the Old Testament, he wondered whether Weizman was alluding to Deuteronomy 6:4: שמע ישראל Shəmáʕ Yisraél (Hear, O Israel). Knowing neither Yiddish, Russian (Что слышно chto slyshno), Polish (Co słychać), Romanian (Ce se aude), nor Georgian (რა ისმის ra ismis) – let alone Israeli (מה נשמע má nishmà) – the professor had no chance whatsoever of guessing the actual meaning (“What’s up?”) of this beautiful, economical expression.

Any credible answer to the enigma of Israeli – as opposed to Hebrew – requires an exhaustive study of the manifold influence of Yiddish on this אלטניילאנג ‘altneulangue’ (“Old New Language”) – cf. the classic אלטניילאנד Altneuland (Old New Land”), written by Theodor Herzl, the visionary of the Jewish State in the old-new land. I analyse אלטניי altneu also as Hebrew על תנאי (Israeli al tnáy) ‘on condition’ [that we embrace the hybridity of the Israeli language]).

At first sight, it appears that Hebrew has killed Yiddish and that, after the Holocaust (and, mutatis mutandis, communism and Zionism), Yiddish was destined to be spoken almost exclusively by ultra-Orthodox Jews and some eccentric academics. Yet, closer scrutiny challenges this perception. The victorious so-called ‘Hebrew’ may, after all, be partly Yiddish at heart. In fact, Yiddish survives beneath Israeli phonetics, phonology, discourse, syntax, semantics, lexis, and even morphology, although traditional and institutional linguists have been most reluctant to admit it. Israeli is not רצח יידיש rétsakh yídish (Israeli for ‘the murder of Yiddish [by Hebrew]’) but rather יידיש רעדט זיך yídish redt zikh (Yiddish for ‘Yiddish speaks itself [beneath Israeli]’).

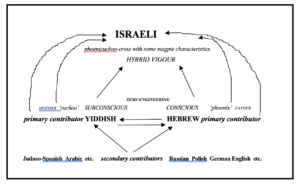

The following figure illustrates the hybridic genesis of the Israeli language:

What makes the ‘genetics’ of Israeli grammar so complex, thus supporting my model of Israeli genesis, is the fact that the combination of Semitic and Indo-European influences is a phenomenon occurring already within the primary (and secondary) contributors to Israeli:

Yiddish, a Germanic language with a Latin substrate (with most dialects having been influenced by Slavonic languages), was shaped by Hebrew and Aramaic.

On the other hand, Indo-European languages, such as Greek, played a role in pre-Medieval varieties of Hebrew (see, for example, Hellenisms in the Old Testament).

Moreover, before the emergence of Israeli, Yiddish and other European languages influenced Medieval and Maskilic variants of Hebrew, which, in turn, shaped Israeli (in tandem with the European contribution).

Taken to its extreme, this approach might lead to the bitter question: ?הרצחת וגם ירשת harotsákhto vegám yoróshto (Israeli aratsákhta vegám yaráshta) (Hebrew for ‘Hast thou killed, and also taken possession?’, 1 Kings 21:19)? But I would advocate a more positive, reconciliatory attitude: cultures – through language – have their intriguing ways of cross-fertilizing and hybridizing, resulting in new diversities. One should not bear a grudge. What one might consider as ‘mistakes’ today might well be the grammar of tomorrow; the stop gaps of the present are the infrastructure of the future. And yet, if you are a mámə lóshņ (Yiddish for ‘mother tongue’)-lover who is reluctant to accept such a liberal view, you might be consoled by the fact that, after all, Yiddish survives beneath one of its ‘killers’, Israeli. Thus, as long as Israeli survives (and American will not kill her during our lifetime), Yiddish survives too.

Concluding remarks

There are various religious elements in the way that Israeli scholars, many of them secular, consider Israeli:

(1) Hebrew and Israeli are one and the same. This can be paralleled to the belief that there is one God;

(2) Israelis must adhere to Hebrew grammatical rules. This can be paralleled to the belief that Jews should follow good deeds (mitzvoth);

(3) The language needs an authoritative institution (Academy of the Hebrew Language). This can be paralleled to the belief that the Jews needed to be controlled by religious leaders;

(4) The Hebrew revival is a miracle. This can be paralleled to the belief in Biblical divine miracles.

All these elements are myths. Israeli linguistic patterns have often been based on Yiddish, Russian, Polish, and sometimes ‘Standard Average European’. This is, obviously, not to say that the revivalists, had they paid attention to patterns, would have managed to neutralize the impact of their mother tongues, which was often subconscious. Although they engaged in a campaign for linguistic purity (they wanted Israeli to be Hebrew, despising the Yiddish ‘jargon’ and negating the Diaspora and the diasporic Jew), the language that revivalists created mirrors the very hybridity and foreign impact they sought to erase. The revivalists’ attempt to

(1) deny their (more recent) roots in search of Biblical ancientness,

(2) negate diasporism and disown the ‘weak, dependent, persecuted, feminine, homosexual’ exilic Jew and

(3) avoid hybridity (as reflected in Slavonized, Romance/Semitic-influenced, Germanic Yiddish itself, which they despised)

failed.

Further reading:

Zuckermann, Ghil‘ad 2020. Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond. Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199812790 (pbk), ISBN 9780199812776 (hbk), https://global.oup.com/academic/product/revivalistics-9780199812790 (Special 30% Discount Promo Code: AAFLYG6)

Zuckermann, Ghil‘ad 2003. Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. London – New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-3869-5, ISBN 1-4039-1723-X.

Professor Ghil‘ad Zuckermann (D.Phil Oxford) is Chair of Linguistics and Endangered Languages at the University of Adelaide, Australia. Since the beginning of 2017 he has been a chief investigator in an NHMRC research project assessing language revival and mental health; as well as the elected President of the Australian Association for Jewish Studies. Prof. Zuckermann is the author of Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2020), the seminal bestseller Israelit Safa Yafa (Israeli – A Beautiful Language; Am Oved, 2008), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 多源造词研究 (A Study of Multisourced Neologization; East China Normal University Press, 2021), three chapters of the Israeli Tingo (Keren, 2011), Engaging – A Guide to Interacting Respectfully and Reciprocally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, and their Arts Practices and Intellectual Property (2015), the first online Dictionary of the Barngarla Aboriginal Language (2018), Barngarlidhi Manoo (Speaking Barngarla Together), Part 1, Part 2 (2019) and Mangiri Yarda (Healthy Country: Barngarla Wellbeing and Nature) (2021). He is the editor of Burning Issues in Afro-Asiatic Linguistics (2012), Jewish Language Contact (2014), a special issue of the International Journal of the Sociology of Language, and the co-editor of Endangered Words, Signs of Revival (2014).

Professor Ghil‘ad Zuckermann is the founder of Revivalistics, a new global, trans-disciplinary field of enquiry surrounding language reclamation, revitalization and reinvigoration. On 14 September 2011 he launched, with the Barngarla Aboriginal communities of Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, the reclamation of the Barngarla language. Professor Zuckermann is elected member of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and the Foundation for Endangered Languages (FEL). He was President of AustraLex in 2013-2015, Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Fellow in 2007–2011, and Gulbenkian Research Fellow at Churchill College Cambridge in 2000-2004. He has been Consultant and Expert Witness in (corpus) lexicography and (forensic) linguistics, in court cases all over the globe. He has taught at Middlebury College (Vermont), University of Cambridge, University of Queensland, National University of Singapore, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, East China Normal University, Shanghai International Studies University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and University of Miami. He has been Research Fellow at the Weizmann Institute of Science; Tel Aviv University; Rockefeller Foundation’s Study and Conference Center, Villa Serbelloni, Bellagio, Italy; Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Institute for Advanced Study, La Trobe University; Mahidol University; and Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyūjo (National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Tokyo). He has been Denise Skinner Scholar at St Hugh’s College Oxford, Scatcherd European Scholar at the University of Oxford, and scholar at the United World College of the Adriatic (Italy).

His MOOC (Massive Open Online Course), Language Revival: Securing the Future of Endangered Languages, has attracted 20,000 learners from 190 countries (speakers of hundreds of distinct languages):

https://www.edx.org/course/language-revival-securing-future-adelaidex-lang101x

http://www.adelaide.edu.au/news/news79582.html

http://www.facebook.com/ProfessorZuckermann

Professor Ghil‘ad Zuckermann, D.Phil. (Oxon.), Chair of Linguistics and Endangered Languages, School of Humanities, Faculty of Arts, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide SA 5005, Australia. ghilad.zuckermann@adelaide.edu.au, +61 8 8313 5247, +61 423 901 808.

See also:

http://adelaide.academia.edu/zuckermann/