Lingoblog is celebrating the summer with a biography of the world-famous linguist Karl Verner in four parts. In case you missed the first two parts, you can follow this link and this link. Don’t forget to read the last part of the series next week.

Back to Aarhus – the location of the great discovery

After finishing his studies, Karl Verner had to return to his hometown Aarhus. There were no financial possibilities for him to stay in Copenhagen. In the Aarhusian carpenter home, Karl Verner had to manage with his family’s help. He earned a bit with bookkeeping and administration for the family store. But most of all, he spent his time on his own studies. In a letter to Vilhelm Thomsen he calls himself the “only non-performing family member”. During this time, Verner’s biggest problem was that there was no university library in Aarhus. The library at the Cathedral School, just a stone throw away from Vestergade, was useless. Because of the lack of books, he could not, as he used to do during his time in Copenhagen, conduct his extensive linguistics studies. Still, he was tirelessly making excerpts from his previous books and writing drafts to linguistic investigations. In the province there was a lack of opportunities for a young academic to advance. There were no colleagues to discuss the results of his extensive studies with. He did not have a study room either.

Karl Verner was disgruntled with everything in Aarhus. He even called Aarhus an “academic desert” in a letter to Vilhelm Thomsen. His family could not support his studies of linguistics. Because of that, he considered in moments of despair to apply for a position at the railroads or as a private tutor on one of the Danish islands. In a letter to Vilhelm Thomsen on the 26th of September 1874, he writes: “At least I comfort myself in that when I will go somewhere, for instance Lolland or Falster where the dialect is interesting and not yet examined, I will be able to paralyze the unpleasantries of being a private tutor and make the year pass”.

Not until he was given a 800 kr scholarship in 1875 and with it a chance to go to Copenhagen for four weeks and use the libraries. There his studies took off again. He was given the scholarship so that he could go to Carthaus in the Danzig area to investigate the intonation in the local Kashubian dialect. In Carthaus, he acted like a true linguist and mostly spend his time at bars where he sat and listened to the Kashubian farmers. He spent the rest of his time in his room and wrote down his observations. Obviously, this behavior had to arouse the police’s suspicion. The police in Carthaus inquired with the Copenhagen police. When no one understood the passport, they received in Danish and French, Verner had to go to the police station. Since no one could read the passport, he had to be his own interpreter. It was not until he showed a letter from a German professor, showing that Karl Verner was a linguist and not a spy, that the police let him go.

The four weeks at the libraries in Copenhagen gave Karl Verner the opportunity to complete the groundbreaking dissertation about the sound shift, which was published in 1876 under the title: “Eine Ausnahme der ersten Lautverschiebung”. Verner himself called it “a footnote”. Following the stay in Danzig, Karl Verner traveled back to Aarhus to the same conditions as he left. In a letter from the 24th of April 1876, he writes to Scherer in Strasbourg that the preoccupation with his “little research articles” is a matter of life and death for him, “to get himself out of the financially poor conditions”.

A librarian in Halle

During the time from 1st of October 1876 to 1st of January 1883, Karl Verner was employed as a civil servant at the University Library in Halle. The University Library in Halle needed someone to update the cataloging. Many Germans wanted the position, and it was remarkable that a Danish applicant was chosen instead. Karl Verner started as a librarian assistant for very little money, but quickly rose in position and ended up as “second custodian” at the library. During his time at the library, he was offered several other better paid positions. Verner’s dissertation had made him so famous in Germany that several universities there wanted him. But Verner preferred staying as a librarian. A job he cared deeply about.

The low pay initially did not allow him to have his own place to live. He had to live in two rooms in the library. Only one had a window to the courtyard, but Karl Verner did not mind because now he was near his books. In exchange for free lodging, he worked as a kind of night watch of the buildings.

For the library’s part, they were exceedingly happy with the young librarian Verner, who from early morning to late at night made himself busy sorting the library books. He was so fascinated by the library vocation that he designed a new system for cataloging the library’s books. A linguist at heart, Verner had chosen only syllables instead of numbers and letters. Every book needed an easily pronounced signature that could not be confused with other books. The system could hold up to 7 million two syllable words. Verner’s practical system was appreciated by his superiors and by his colleagues, but the library did not end up using it. In the end, it would be a costly affair to rearrange the many books in the university library.

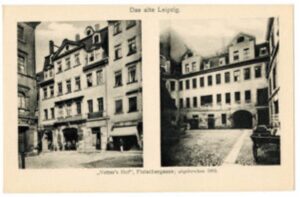

During his time in Halle, Verner got to know the young linguists from the University in Leipzig, the so-called Neogrammarians. This circle of young scientists had new ideas about the evolution of languages, and Verner quickly became part of this circle of like-minded people. Contact with the young scientists meant a lot to him, and many friendships were maintained throughout his life. He frequently participated in the Neogrammarian gatherings at the Caffeebaum café in Leipzig. Here, discussions on linguistic topics were the center of attention. It is a fact that Karl Verner once more discovered a law in the evolution of language: The so-called palatal law. I will not go into it in detail here. However, as usual Verner was content with explaining it to his friends, who then went home to write about it. For Verner it was enough to have found the solution to a problem. Only through references from other linguists to this incident at the stairs of the Caffeebaum, we know that the discovery was Verner’s achievement.

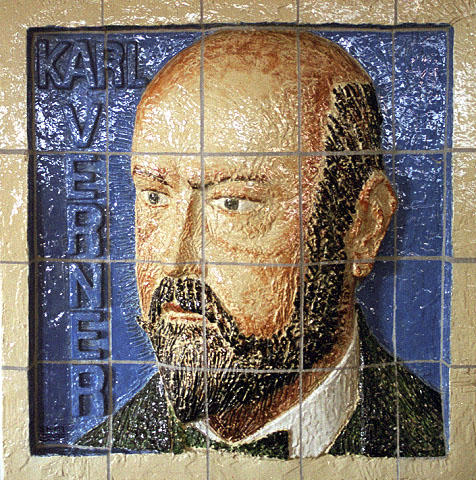

Frontpage picture: The sculptor Knud Nellemose’s stoneware relief. On display at the Verner-room in Nobelparken, Jens Chr. Skous Vej, Room 366, Building 1481.

The article “Karl Verner – A world-famous student” has previously been published in the book Aarhus Cathedral School, 1195-1995, edited by Finn Stein Larsen. Aarhus: Aarhus Cathedral School, 1995.

Lars H. Eriksen. Born in 1957, graduate with A-levels in modern languages from Aarhus Cathedral School in 1976, studies in Nordic, linguistics, Germanische Philologie as well as studies in law, tax law and economy at the University of Aarhus, Universität Düsseldorf, Universität Bayreuth and University of Southern Denmark. Cand. phil i dansk 1982, Ph.d. 2001 on a dissertation on “The language of the court in Denmark and Germany” (“Sprache vor Gericht und in der Verwaltung”) – Associate professor in Danish in Bayreuth 1980-90, law. in Bavaria 1990, then Rechtsreferendar in Bayreuth, employee at law firms in Düsseldorf, Saxony and Bavaria. 1996-2001 University lecturer in Danish and German at the cross-border studies in Sønderborg and Flensburg. Collaborator on international language projects on language policy and language law; tax law, EU corporate tax law and criminal law. Employee at the European Commission on International Social Security. Now working as a tax consultant in international affairs in South Schleswig. Has written articles on German and Danish language matters, language teaching and legal topics. Publisher of several Danish-German dictionary works within law and tax / annual accounts 2016-2021