There’s a particular experience that I have encountered many times during my life, and which you might recognise from your own, that I tend to think of as ‘the geographic eureka’. I’m walking in an area that I’m familiar with, and I decide to stray from the path I know in order to explore some road less travelled. I’ll walk around for a stretch of time, every turn or fork in the road leading me to new areas with varying degrees of interest, and eventually I turn the corner that, completely unexpectedly, puts me back on familiar territory; which is when the feeling hits me: “Oh, so that’s where I am!”. Peter Trudgill’s newest book, European Language Matters, consistently gave me the linguistic equivalent of this experience. If it’s not clear what I mean by this, hang on – I’ll clarify in a moment.

The full title of the book is European Language Matters: English in its European Context, and that subtitle is a very accurate description of the book’s subject. Although the broader subject is European languages in general, the book is written by an English linguist working in England, writing in English to a mostly English audience – so it’s no surprise that Trudgill chooses to use the language he shares with his readers as the crux of his perspective. Despite this, the book always keeps the variety of Europe’s linguistic landscape in mind, constantly drawing on examples from many different languages. As a result, the book’s proclaimed focus on English feels less like an ode to the lingua franca, and more like a simple practical consideration in sharing this knowledge with the reader – which is a good thing, as far as I’m concerned.

Before I delve further into my experience and opinions, let’s establish what the book actually is. European Language Matters contains a collection of mini-essays written by Peter Trudgill over the course of four years, originally released as a weekly column in the magazine The New European. For the 2021 publication, the columns have been edited and sorted into fourteen different categories based on their topics. I was lucky enough to be offered a copy of the book for review purposes, which has since become charmingly battered – something which I personally blame on the book’s fragmentary nature. Since each column is only about a page long, the book lends itself perfectly to reading on the go: On the bus, on a bench in the park, or in the university reading hall when you really ought to be working on your exams. Consequently, I have been carrying the book with me almost everywhere since receiving it, exposing it to the elements and (what’s arguably worse) the various contents of my bag and my pockets.

Before I delve further into my experience and opinions, let’s establish what the book actually is. European Language Matters contains a collection of mini-essays written by Peter Trudgill over the course of four years, originally released as a weekly column in the magazine The New European. For the 2021 publication, the columns have been edited and sorted into fourteen different categories based on their topics. I was lucky enough to be offered a copy of the book for review purposes, which has since become charmingly battered – something which I personally blame on the book’s fragmentary nature. Since each column is only about a page long, the book lends itself perfectly to reading on the go: On the bus, on a bench in the park, or in the university reading hall when you really ought to be working on your exams. Consequently, I have been carrying the book with me almost everywhere since receiving it, exposing it to the elements and (what’s arguably worse) the various contents of my bag and my pockets.

My experience of reading this book was, like the book itself, manifold. But perhaps the most consistent part of it was the feeling of moving along a path – either a path of association, the path of a language as its speakers travel geographically, or most often, the etymological path of a word or term. And almost unfailingly, Trudgill would lead me along this path through unknown territory, only to emerge at the end to understand how that word, language or theme connects to some other familiar word, language or theme. And that’s when I would invariably yell out in my mind: ”Oh, so that’s where I am!”

One of literature’s greatest insights into the human condition is the observation (here slightly paraphrased) that ”I’d prefer to hear a story about myself”. As a native speaker of Danish, Trudgill’s tales of the European linguistic landscape is most definitely a story about myself. And that’s part of the allure of this book: Any European – or more accurately, anyone who even speaks a European language – can find a personal connection to this book’s contents, and will most likely learn something about their own culture and history. Because, as the book demonstrates time and time again, the history of a language is not a solitary thing, but a history of peoples interacting; and you can’t discuss the history of English without discussing the history of Danish, French, Latin, Greek, Scots, Gaelic… you get the picture.

Being a collection of individual columns, the book unavoidably repeats itself many times, but this is less of an issue than it could have been. Several columns might refer to the same historical events, but always with a new point to demonstrate or story to tell, and the effect is that, rather than feeling repetitive, we get a fuller understanding of these events by seeing so many of their linguistic consequences.

It is also worth noting that Trudgill is not afraid to share his opinions about the events he describes. Trudgill takes up the fight against political figures such as Franco, Trump and the anti-scientific division of the Serbocroatian language, while praising figures like the Aotearoan prime minister Jacinda Ardern in flowery language (that’s a pun – the name ‘Jacinda’ is etymologically related to ‘hyacinth’, as Trudgill explains). Ironically, this is not so much the case in the chapter titled ‘Pedantry and Persecution’. This chapter mainly deals with linguistic prescriptivism, but for a sociolinguist, that’s really the bare minimum – especially compared to Trudgill’s personal involvement in sociolinguistic causes described in some other chapters of the book. All in all, though, Trudgill’s clear stance-taking comes across as well-informed and sympathetic, and lends a sense of purpose to the book beyond simple entertaining us language nerds.

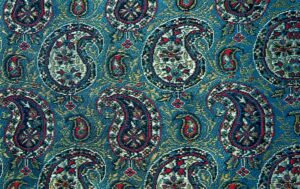

If I have any complaints about this book, they’re minor. Mainly, I think the book would have benefited from a few illustrations. As I’ve said, the book relies a lot on geographical descriptions, and for those of us who are a little foggy about exactly which countries border which, just a single map of Europe in the beginning of the book would have been a great point of reference. But even non-cartographic illustrations would have been an advantage. For example, one of the columns discusses the so-called ‘Paisley pattern’, while another describes the look of the ancient script known as Linear B. Both of these things would be much more efficiently communicated with a simply illustration next to the text.

Trudgill also fleshes out the columns with a new introduction to the book, as well as individual introductions to each of its chapters, so it seems like a missed opportunity to not also round off the book with an afterword. Perhaps a call to action, perhaps a reflection on the wonderful variety of language, or perhaps just personal musings about the author’s experience as a columnist. As it stands, the book ends quite suddenly and unceremoniously. But as I say above, these are of course very minor criticisms, and the book is still a very worthwhile read as it is.

This brings us to the basic question any review must answer: Who is this for? If you’re a linguist, this book will probably contain a bunch of information you already know, but probably also a lot of things you don’t. For a lay reader, the book may be a little heavy on linguistic theory and terminology, but Trudgill holds your hand along the way and ensures that each column can be understood as a stand-alone piece. So all in all, I don’t think your level of linguistic expertise matters all that much when it comes to your enjoyment of this book. Either way, you’re bound to learn something new, and to be able to follow along with just a bit of effort. All you really need to enjoy this book is an enthusiasm for language, culture and history. And perhaps a daily commute.

Gustav Styrbjørn Johannessen is a Master’s student of linguistics at Aarhus University, and has written several book reviews for Lingoblog.dk. He is doing his best to spread knowledge of linguistics through talks, writing and workshops.