A little more than a year ago, I wrote a Lingoblog article recommending a selection of books discussing various topics in linguistics from a pop science perspective – that is, books that are about technical aspects of linguistics, but which can be understood without any prior knowledge of the field. Since these past twelve months have, for many of us, taken place largely inside the same four walls, there has (to look on the bright side) been plenty of time to read.

True to form, a handful of the books in my personal reading pile has been about language and linguistics. My previous article was sparked by my conflicted feelings about Daniel Everett’s Language: The Cultural Tool, and I have now read another book that made my linguist heart overflow with opinions and questions best expressed in the form of a blog entry (you may be able to guess which of the following books I’m referring to here!). That’s why I’m taking this opportunity to add yet another five books to my recommendations from last year:

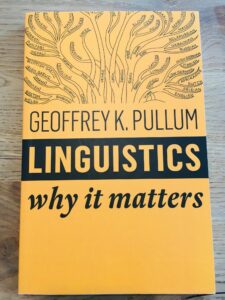

GEOFFREY K. PULLUM: LINGUISTICS: WHY IT MATTERS (2018, 123 pages)

As a student, particularly in the humanities or less widely known sciences, you quickly get used to the question “How can you apply this knowledge in real life?”. It’s nice for a linguist to keep a handful of Practical Applications in mind to refer to whenever someone implies that your education requires something as pedestrian as a purpose. There are certain classic answers to give, such as language teaching, speech therapy, editorial work and forensic linguistics. But after giving the same answer more than a few times, it can start feeling a bit artificial if you don’t have a way to build on the subject.

This is where Geoffrey Pullum comes to the rescue. In Linguistics: Why It Matters, he walks the reader through a handful of practical uses of the sort of knowledge that linguistics retrieves. Pullum makes it clear in the introduction that this is his personal selection of topics, and those topics show to varying degrees both how exciting and useful it can be for us to know things about language. To the experienced linguist, the book doesn’t contain much in the way of new information, but to the average language fan who’s curious to learn more, the book is an ideal resource. It is a well-written and very quick read, but will give you a solid impression of some of the uses of linguistics.

This is not to say that the book is entirely useless, even if you already know all the basics. Although I personally believe that interest alone is enough justification to study a science, it is also important to put thought into the consequences of one’s participation in said science. To me, this book has been a valuable tool in laying a well-considered foundation for my own future work as a linguist. A book doesn’t necessarily have to present new information – sometimes it is thought-provoking enough to be presented with familiar ideas in a new context.

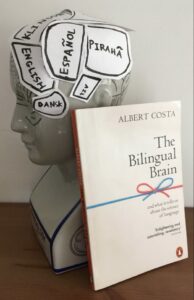

ALBERT COSTA: THE BILINGUAL BRAIN (2020, 148 pages)

‘The bilingual brain’ is a divisive topic. Through the years, many conflicting theories have been proposed about how the human brain is affected by housing more than one language. The main point of discussion is whether bilinguals are more or less intelligent than monolinguals, and whether it’s more ‘natural’ to speak one language or multiple. The scientific grounds for these claims vary wildly, but common for nearly all of them is the fact that they’re motivated by social or political attitudes to particular groups of bilinguals, rather than by a scientific approach to the underlying reality. To put it in other words, this topic is a figurative minefield.

This just makes it particularly impressive how skillfully Albert Costa navigates it in his presentation of the effects of bilingualism. Costa does not lean on the common presumption that bilinguals must necessarily be worse at their languages than monolinguals, but also avoids the opposing sensationalist idea that bilinguals are, by definition, smarter than monolinguals (beyond having access to multiple languages). Instead, he presents a progression of relevant studies, which sometimes point to one conclusion, sometimes to the other. Costa openly criticises the studies he cites, and avoids exaggerating the conclusions in either direction. It’s obvious from the text that Costa has deliberately avoided saying anything other than what is directly supported by studies – and even when it is, he remains appropriately sceptical.

The result is a picture full of nuance – one, which paints bilinguals neither as ‘worse’ language users or some kind of cognitive superheroes. Bilinguals, alongside monolinguals, are viewed as simply people – but that doesn’t mean that the result of the studies described in this book aren’t exciting in and of themselves. Costa demonstrates how bilingualism is characterised by certain cognitive and neurological traits which may be able to teach us much about the nature of language in the human brain.

So far, I have emphasised the scientific integrity of Costa’s writing, because that’s a fundamental thing to have under control when writing about a highly debated topic. This might have given you the impression that this is a very technical book – which, in a way, it is. The book systematically discusses five big questions about bilingualism, and draws on a lot of research, so the reader should be prepared to handle a certain amount of experimental psycholinguistics. At the same time, Costa uses a lot of examples and anecdotes from his own life, as well as pop culture references such as the iconic Babel Fish of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame, giving the book a relatively light and sympathetic tone. It is also not a very long book, so it should be approachable to a reader with even a passing interest in reading about experimental brain science. I strongly recommend this book for anyone with an interest in the subject!

DAVID ADGER: LANGUAGE UNLIMITED (2019, 251 pages)

Language Unlimited is a great title, and honestly, I would have liked to be the one who came up with it. Reading David Adger’s book, however, it gradually becomes clear that a more accurate title would have been ‘Language Formally Limited, But Capable Of Creating Unlimited Output’ – though I do admit that this would have been somewhat less catchy.

If the sentiment behind that alternate title sounds familiar, that’s because it’s one of the fundamental observations of linguistics: That language, as a phenomenon, uses a limited set of formal entities to create an unlimited range of potential outputs. This idea is particularly important to the generative branch of linguistics, and this is the direction from which Adger approaches the subject.

The book presents the basic principles of the most recent widely used incarnation of generative grammar, and the key concept is therefore the merge – something which I had personally seen referenced often, but which I hadn’t read any dedicated explanations of until this book. Adger builds up to the concept by first explaining a series of more basic concepts in grammatical analysis, including a bunch of the classic tree diagrams as illustrations. The book also presents and discusses a few different aspects of syntax, such as some different approaches to the cognitive mechanisms behind it; the implications of the difference between understanding of syntax in humans compared to other animals; and humans’ attempts to create computer algorithms to parse syntax in a manner similar to that of the human brain. These topics are all tied together in Adger’s overarching argument that grammar as a phenomenon is best explained by that single central function – Merge.

The book undisputedly gives an impressive overview to the newcomer of the theory it presents. It’s easy to read, and does not assume any previous technical knowledge on the reader’s part. Still, my recommendation of it to the lay reader is not unconditional. As someone who has already been trained to a certain extent in grammatical theory and analysis, but not in the generative tradition, I personally felt I learned a great deal from this book. Language Unlimited has given me a better understanding of the theoretical framework in which a significant portion of modern linguists are working. However, to a reader with less previous understanding of linguistics, I would recommend a critical attitude while reading. This is because Adger presents generative theory as something entirely uncontroversial – as though it were simply the only logical conclusion. This is done in part by creating straw man arguments on behalf of non-generativist linguistic traditions. That’s why I strongly recommend the book to people in my own situation: Those who are curious about the generative approach, but also well-versed enough in grammatical theory to be critical toward the author’s arguments.

Alternatively, I recommend reading the book alongside one of the books I recommended in my previous blog entry: Daniel Everett’s Language: The Cultural Tool. Both of these books are well-written, and they each argue on one side of the issue of generativism. Both books would benefit from a more nuanced approach to said issue, though – which makes them ideal to compensate for each other’s shortcomings, allowing the reader to achieve an academically solid confusion, rather than comfortably unnuanced certainty.

RAY JACKENDOFF: A USER’S GUIDE TO THOUGHT AND MEANING (2012, 247 pages)

Ray Jackendoff’s book A User’s Guide to Thought and Meaning is above all else about cognition: The inner workings of the human mind, and how what we experience as consciousness is formed. My first impression of the book was as follows: The physical object itself is surprisingly neat for a non-fiction book. The hardcover version is completely black, with the title in gold letters on the spine. The dust jacket is a simple design with purpley-orange watercolours, making it nice to look at and giving it an – in lack of better words – friendly look. However, the book is also covered in praise from Steven Pinker, so already before opening the book, my feelings were mixed.

These mixed feelings turned out to be representative of the book as a whole. Unlike most pop linguistic publications, this isn’t a presentation of many different people’s research, but rather of the author’s own theoretical work. Jackendoff explains in the introduction that his theoretical models are explained in more detail in some of his previous books, whereas this book is intended as a more approachable introduction to the theory for the lay reader. The result of this dedication is a careful, effective structure: Each chapter, only a few pages long, explains a single point, which the following chapters build upon in turn. This structure takes a little getting used to, but in the long run it makes it much easier to follow Jackendoff’s complex and abstract discussions of cognition and philosophy. Readers who are already familiar with cognitive linguistics may recognise this type of structure from Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By.

Jackendoff’s written voice is witty, sharp and very confident – to the point where it can at times be read as arrogance (although I freely admit that my impression here may be coloured by my mixed feelings from the get-go). Jackendoff often refers to other researchers, writers and philosophers, but rarely without explaining exactly how he disagrees with them. As an alternative, he offers up his own model of the human mind, in which he uses language to explore a number of questions which are more or less crucial to the human experience. During this exploration, he draws a number of conclusions, with which I personally agree in very varying extents. For example, I highly appreciate his considerations on the different perspectives used to construct the world, but less so the conclusions he draws from his observations on the linguistic skills (or lack of the same) of animals.

In the end, I can’t declare any unwavering excitement, nor any undivided disappointment in A User’s Guide to Thought and Meaning. I do, however, recommend it to anyone who’s interested in a fascinating set of considerations on what it means to possess consciousness.

DAVID SHARIATMADARI: DON’T BELIEVE A WORD (2019, 275 pages)

Last, but not least: A book about language myths! Personally, I appreciate any effort to address the myths and misunderstandings that exist about language, and I have to admit that this is exactly the kind of book that I wish I’d written myself. Each chapter takes on one common misunderstanding, drawing on relevant knowledge from linguistics to set it right. Most often, the conclusion is more complex than merely “This is right” or “This is wrong”, and Shariatmadari excellently juggles the technicality of the topics with the approachability of his writing.

Like with Linguistics: Why it Matters, I’d like to disclaim that this book is unlikely to contain any major new knowledge for the reader who is already familiar with the field of linguistics. However, it does present this knowledge in an interesting and understandable way, and even puts it in a context where it can answer some of the questions that many people may have been wondering about language. I very strongly recommend the book to those readers who are curious about language without necessarily knowing a lot about its technical aspects.

It should be mentioned that this book does have a not entirely uncontroversial agenda. The final chapter of the book adresses the myth that “Language is an instinct”. This chapter is a direct reply to Steven Pinker’s 1994 book The Language Instinct, which is among the best-selling pop linguistics publications ever. Due to the book’s popularity, Pinker’s claims are relatively commonly known among people who enjoy reading about language psychology without necessarily having formal education on the subject. That’s why it may come as a surprise to many that far from all linguists agree on Pinker’s ‘language instinct’ hypothesis.

By addressing this hypothesis on par with other claims that are undisputedly false, Shariatmadari is taking a clear stance on a debate which has been going on for decades. Personally I believe that it’s a good thing for the lay reader to be made aware that Pinker’s claims aren’t gospel in scientific circles; but of course, this is all a matter of personal academic stance. In any case, it’s good for the reader to know in advance that Shariatmadari’s stance in this case is not unanimously accepted among linguists – just like the stance he is opposing isn’t.

To sum up, Don’t Believe a Word is entertaining and educational for anyone who isn’t already trained as a linguist, resulting in a formidable feat of linguistics pop literature.

Have I tempted you to read any of the books on this list? Or, if you have already read any of them, what did you think of them? Are there any other books about linguistics that you would like to recommend? If you leave your thoughts in the comments below, I’d be pleased to read what you have to say! And beyond that, I simply hope some of you have found some inspiration for future reading in this post.

Happy reading!

Gustav Styrbjørn Johannessen is a recent BA of Linguistics, and will be a Master’s student of the same field in the near future. His experience communicating linguistics comes from Linguistic Mythbusters and Det Rullende Universitet, as well as from administrating the facebook group ‘Linguistics Book Club’.