Not long ago, I wrote a review on Lingoblog.dk, discussing Nolan’s (2020) book The Elusive case of Lingua Franca. That book was an open-ended study akin to an enchanting yet frustrating detective novel, in search of the famous contact language of the Mediterranean. It discusses the difficulties in tracing that famous ‘mixture of all languages, by means of which we can all understand one another’, ‘that all over Barbary and even in Constantinople is the medium between captives and Moors, and is neither Morisco nor Castilian, nor of any other nation’, as Miguel de Cervantes describes in Chapter XLI of the Don Quixote, most probably, the “Lingua Franca”.

Cervantes wrote the masterpiece of Don Quixote after he himself had been held hostage for five years, in the Barbary Coast slave colony of Algiers (1575-1580). In this Ottoman Empire owned slave colony of North Africa, a common language called Lingua Franca was used with the Christian/European slaves, as was reported by many eye and earwitnesses. Despite Cervantes’ prolific writings, only very few traces of Lingua Franca language samples are left in his work, such as repetitions of the abusive shouts “perro, cane” from the mouths of the Ottoman empire based slave holders. A contemporary of Cervantes, however, reported in great detail about the so-called Baños de Argel, the main headquarters of slavery on the much feared “Barbary Coast” of North Africa. Under the guise of Haedo (1612), that contemporary now shown to have been a certain Do Sosa, published the “Topographia e historia general de Argel”, providing some very interesting LF samples:

“Dio grande no pigllar fantesia, Mundo cosi cosi. Si estar scripto in testa, andar, andar. Si no aca morir..”

(God is great, do not be fooled by your imagination: The world is now this, now that. If it is written that you will go, you will go. If not, here you will die.)

Lingua Franca (LF) was said to have been freely composed of a variety of languages, the vocabulary culled mainly from Romance languages such as Spanish and Italian, though any foreign admixture – Arabic, Turkish, Germanic – was admitted to the treasure trove of contact language expression. The resulting language has fascinated observers near and far for well over 400 years, taking on mythical proportions.

Indeed, both mythical and elusive, we quite concurred with Nolan’s reiteration of this disappointing conclusion. Being an extinct oral language, LF is, to a large extent, unknowable to us – just like the Loch Ness monster, the seasnake that everyone has heard of yet noone has properly seen, as I, too, argued myself in Scotland 2004. LF shall never be properly described, we all sighed.

In 2021, California-based Operstein rolled up her sleeves and got down to business of taking investigations of two primary sources to the next level. As a result, she seems to have proven this conclusion eminently wrong. In the book under review today, Operstein (2021) provides an in-depth grammar of the infamous and long defunct Lingua Franca of the Mediterranean (LF) – and has thereby accomplished an amazing feat that the field of Pidgin and Creole languages has waited on for over a century.

To recap once more: Lingua Franca is the early contact language that was purportedly spoken throughout many centuries, from at least the 15th to the 19th century, along the littorals of the Mediterranean Sea, as well as land-inwards, and also aboard ships roaming the sea itself. This we know from a myth that has been spun and spun again for – actually, the same time span. LF was infamous from the start of the historical records that mention it. And there are plenty. Why then everconsider LF elusive?

Well, the language simply was not used as a written medium, as far as we can tell, and many a researcher has looked through many an archive for further traces. No voice recorders back then, no surviving speakers (though I once went looking in Melilla, the Spanish enclave in North Africa not too far from Algiers, on a hunch of Ur-creolist Schuchardt’s comment in his seminal publication of 1909: again, no trace to be found). The sources of LF we do have are abundant in the sense of word count – around 10,000 canonized words, if you will. For a pidgin, that is a lot. For an unwritten language, even more. However, the sources’ origins are strewn across five centuries, and the entire Mediterranean area. These sources are most often literary, and the ones that can be considered documentary are of uncertain status, often seem copied from another source, or are extremely brief. Amongst the many genres that seek to represent LF, reearchers have included songs, poems, theatre pieces, travelogues, and reports of enslaved Europeans finding themselves in Algerian captivity. None of the sources can be considered straightforward reflections of LF, and many of them seem to take on the nature of caricatures.

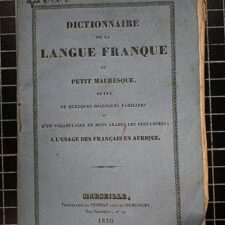

Yet, there is, at the very end of our trickled trace of evidence, also one quite substantial source: a dictionary! Where there is a dictionary,there must surely be a language ? ‘Le Dictionnaire de la Langue Franque ou Petit Mauresque […]’ (Dictionary of Lingua Franca or the little moorish language […]), was anonymously authored and published 1830 in Marseille by Feissat &Demonchy. It is easily accessible, to be found in the national libraries in both London and Paris, and now even digitally at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6290361w/ . It remained contentious.

Where a publication is anonymously authored, and contains numerous internal discrepancies, that work stands on much shakier ground. It was conjectured that several authors may have been at work, and remarked that it had been all too hastily compiled. The uncertain authorship and unclear origins of this often celebrated source much diminished its authenticity. Operstein has now brought this Dictionnaire to the light of day.

The Dictionnaire is a treasure trove of most distinguished dialogue, from basic forms of politeness to adament expression of doubt:

Mi poudir servir per ti per qualke cosa? (May I serve you anything?)

Mi non credir ouna palabra (I do not believe a word.)

Despite many widespread efforts to uncover new materials in order to truly substantiate and illustrate what the nature of LF was, we were always left feeling like we cannot grasp LF. So, after over 100 years of close research since the 1909 seminal paper “Die Lingua franca”, written by the first ever contact language specialist, Hugo Schuchardt, we were almost ready to throw our hands up, if not in despair, then in submission to this simple fact: LF would never have its own grammar, and remain hidden for ever in the obscurity of myth.

Not so.

Natalie Operstein has thrown the gear into reverse, sending doubt and uncertainty overboard.

In this heavy, handsome hardcover 405-page book, Operstein cleans up with myth. Cool as a cucumber, Operstein proceeds step by step. She 1. uncovers the author of the dictionnaire; 2. identifies two models of didactical grammar writing that the Dictionnaire was modelled on; 3. writes a fine-grained grammar of the language that many have considered impossible to describe; and 4. ends by placing LF into theoretical context.

The book opens with a huge discovery in entirely level-headed discussion: Operstein coolly and convincingly reveals the author of the Dictionnaire as one William Brown Hodgson (1801-1871), the US State Department’s first officer on a language-training mission in Algiers from 1826-1829. The masterful historical detective work behind this discovery is done almost entirely in the off. How she has managed to identify Hodgson we do not know; though discovering him must have involved casting huge dragnets indeed. When she further identifies the conceptual models he must have used in ushering this book to completion, as two works written by Vergani and Veneroni, the days’ most popular teaching books of Italian, by showing the often one-to-one correspondences to these works, as well as clearly indicating the simplifications of the conversational and lexical templates, – and in addition supporting this comparative study of content and structure with a record of Hodgson’s personal book orders, – we feel like she visibly pulls away the dusty curtains of the past. Immersing us in Hodgson’s personal history like it were today, Operstein shows us just what happened, off the written page of the Dictionnaire. The structure of the Dictionnaire so strongly ressembles Vergani’s 1823 book that we see how rapidly it could have been calqued upon: Operstein proposes that the Dictionnaire was written within the first year of Hodgson’s stay in Algiers, thus, between 1826-1827. Operstein remains entirely level headed about these phenomenal discoveries, and remains very matter-of-fact throughout the book, with the modesty of the true erudite. She simply skims off the cream of her labors and presents them to us.

Her factual tone is well measured and although primarily intended for a linguist audience, her sound reasoning is so clear so that anyone caring to read about LF will find the book accessible. Her referencing is rock solid and thorough. For those wanting to know more, they will get the necessary references to the full panoply of literature on LF.

Operstein is fully engaged in the field of previous LF study, and harnesses the tools of other areas of linguistics in order to seize the nature of LF: Romance Studies, delving into both dialectal and historical realms of the Romance languages; Creolistics with its manyfold approaches; Functional Grammar; and Language Acquisition, among others. This is how she offers a grammar that is both descriptive and comparative, and how she can rightfully propose adjustments and unifications to the theoretical frameworks used for describing contact languages.

Meticulously reasoned, superbly researched, eloquently written, she brings organization into the messiness of LF documentation and analysis. She draws on Haedo (1612) mentioned above as another important, though more limited, earlier source of LF data for further comparisons. Every abberrance is mentioned and accounted for, within the nomenclature of pidgin and creole studies. The findings of other scholars in various subfields are scientifically harvested and incorporated in the thorough search for answers. Careful diachronic and synchronic explanations on all levels of analysis are proposed. Yet, Operstein does not engage in problematizing. She puts labels on variables. From acrolect to basilect, from Foreigner Talk to Language Acquisition data, from pidgin to koine, she wields the toolbox of the contact linguist with greatest precision. And builds carefully and respectfully upon the work of others with pure exacting scientific optimism.

This is linguistic science par excellence, and scholarship at its best.

Operstein has left no stone unturned. She has pulled off what seemed impossible: She has written an in-depth grammar of Lingua franca, the enigmatic contact language that has been long seen as intangible and elusive. In doing this, she not only places the oldest pidgin back on a clean new shelf, she also writes what must be seen as the first thorough pidgin description in the English language, ever.

She has managed to do what enthusiasts and scientists have pined over for centuries:

To conceive a grammar of a language which was based on flexibility.

It is here that an ounce of my scepticism kicks in: What if she has pinned down one rare butterfly for us to behold in all its detail, and we lose sight of its very flight? Will a butterfly pinned down allow us to see how the fluttering happens? No. We simply cannot have it all. The flexibility and souplesse so characteristic of contact languages cannot be contained in a grammar.

Will we ever be able to do justice to a dead oral language? Does a grammar no matter how fine bring us closer to understanding the mechanisms at work in language contact? All these questions may come later. First things first: Here we have, at long last, an offering that the field has been waiting on for over a century.

This book is interesting for any lover of language and detail. It is a fine example of grammar writing, and a fine comparison of a contact language with its lexifiers. It is absolutely indispensable for anyone interested in the Lingua Franca, or in pidgins and koines. It is the new Opus Magnum on this long elusive code. An amazing feat has been accomplished.

Operstein, Natalie. 2020. The Lingua Franca: Contact-Induced Language Change in the Mediterranean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/the-lingua-franca/33422373D9C766A476CE143258F62438

Rachel Selbach is a creolist who has been trying to tame the monster of Nessie for nearly two decades herself. She has made several stabs at describing the enigmatic monster and its historical sightings through a number of articles, and she is still not ready to let go of her personal quest to attain a fuller understanding of Lingua Franca throughout its 500 year existence. Though perhaps, she feels, she is fighting not a seasnake but windmills.

Hi,

I just wanted to reach out and let you know that your content has been quite helpful for me.

My friends from Allthingsaustria recommended your site and I’ve not been disappointed at all :)

Cheers,

Mihkael Caron