The kingdom of Mbessa was founded in the 18th century (circa 1772) by an exiled Nkar man called Tfukenu and a self-exiled Oku prince called Nsuung Nyiete (Mala 2013). Geographically, Mbessa is located between Akeh, Din, Kom and Oku, all of which are neighbouring Fondoms.

Mbessa is found in a rural setting and some of the principal activities practised by Mbesa people are food crop cultivation (e.g., maize, beans, Irish potatoes, bananas), cash crop cultivation (e.g., coffee), animal breeding (e.g., goats, sheep, fowls, pigs), bee farming, weaving, and wood carving, to name but these (Mala 2013).

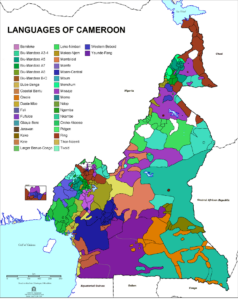

The Mbessa language (Mbessa for short) whose autonym is Iteangh’a Mbessa (or Iteangh’a Mbesa) is one of approximately 300 languages spoken in Cameroon – a central African country which is officially bilingual in the two colonial languages English and French. The immediate linguistic neighbours of Mbessa are Kom, Noone (spoken in Din), and Oku. Mbessa/Mbesa in Cameroon should not be confused with Mbesa (language and village) in DR Congo and other places called Mbesa in Kenya and Tanzania.

In Cameroon, Mbessa, Kom and Oku are all Bantoid languages which belong to the group called Centre Ring. The linguistic relationship between these three Bantoid languages is very much similar to the one between the three Scandinavian languages Danish, Norwegian and Sweden. In fact, while Mbesa, Kom and Oku share some degree of mutual intelligibility, each of these three languages has its own distinctive features that make it a language in its full right.

That notwithstanding, Mbessa (wrongly spelled as Mbizenaku and Mbizinaku) was initially registered as a dialect of Kom under the Kom ISO 639-3 code without the consent of the Mbessa people (Piron 1997, Paulin 1995). It is worth noting that “ISO 639-3 is a set of codes that defines three-letter identifiers for all known human languages” and the Administration or Registration Authority for the ISO 639-3 system is SIL International.

To correct that error of placing Mbesa under Kom and assert the linguistic independence of Mbessa, the Mbessa people through the Mbessa Language Committee (MBELAC), led by Nsah Mala, applied for their own ISO 639-3 code in 2020 and obtained it in 2021 as emz. Thus, since 2021, the ISO 639-3 code for Mbessa is emz and the Glottocode for Mbessa is mbes1239. This landmark victory attests to the international recognition of Mbessa as a distinct language. Metaphorically, one could say that Mbessa has successfully refused to be swallowed by Kom. Mbessa is a full language in its own right.

As it is the case with all ethnolinguistic groups in multilingual societies like Cameroon, Mbessa remains the main language spoken in Mbessa Fondom, but many Mbessa people are multilingual. In terms of multiculturalism and multilingualism, it is important to note, once more, that about 300 languages are spoken in Cameroon (Good 2017, Achimbe 2013, Ayafor 2005). In this regard, English is the main language of instruction in Mbessa schools as of now. However, following recent changes in government language policy in Cameroon (e.g., see Moki 2020, Yaro 2020, Henry 2017), there are plans to make Mbessa the language of instruction in primary schools in Mbessa Fondom once the language is significantly written down. That said, the other languages that some Mbesa people speak include Oku, Noone, Kom, Fulfulde, Bum, Lamnso, Pidgin English, and French.

Let us now have a quick taste of Mbessa. Here are some example sentences in Mbessa:

Ve ke bimeh se ney ifel ateyn. = He/She has accepted to do the work.

Ve | ke | bimeh | se | ney | ifel | ateyn |

He/She | has (aux.) | accept(ed) | to | do | work | the/that |

Ma ke chua ghaynte wa. = I will visit you.

Ma | ke | chua | ghaynte | wa |

I/Me | will (aux.) | will (aux) | visit | you |

Wa ke fa chuo. = You will not go down.

Wa | ke | fa | chuo |

You | will (aux.) | not | go down |

Mbessa neng ilak ijunghi. = Mbessa is a good village/kingdom/fondom/country.

Mbessa | neng | ilak | ijunghi |

Mbessa | is | a village / kingdom /fondom / country | good |

Aluma ne kele aghoyna/awona aboa. = Aluma has two children.

Aluma | ne | kele | aghoyna/awona | aboa |

Aluma | now (aux.) | has | children | two |

Before concluding, it should be noted that the majority of indigenous Cameroonian languages have not yet been written or documented. Such is the case with Mbessa. Some examples of well documented Cameroonian languages include Lamnso, Kom, Oku, Mungaka, Duala, Ewondo, Fulfulde, Ghomala, Bassa’a, and Bamum, to name but these.

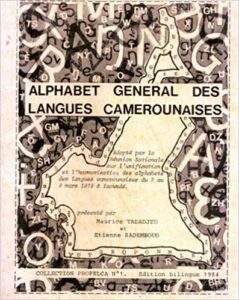

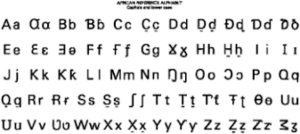

Nearly all of these documented indigenous Cameroonian languages base their orthographies on what is called the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages which is premised on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The major drawbacks of the use of the IPA-derived alphabets for Cameroonian languages are as follows: the indigenous language users require special keyboards before they can effectively communicate by writing and such keyboards are not easy to come by. Moreover, even people who are already literate in English and/or French, still find it very difficult to read and write their indigenous Cameroonian languages because they are not familiar with IPA symbols.

In view of such difficulties, the Mbessa Language Committee (MBELAC) is currently revising the initial Mbessa alphabet that was IPA-based into a Latin-based alphabet. We are drawing our inspiration from popular and widely-spoken African languages such as Chichewa, Kiswahili and Lingala which (mainly) use Latin-based alphabets and are relatively easier to read and write, especially in today’s digital age. We do hope that the forthcoming Latin-based Mbessa alphabet will facilitate the documentation, reading and writing of Mbessa, and contribute in preserving our language and promoting global linguistic diversity.

References:

Achimbe, Eric. 2013. Language Policy and Identity Construction: The Dynamics of Cameroon’s Multilingualism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ayafor, Isaiah Munang. 2005. “Official Bilingualism in Cameroon: Instrumental or Integrative Policy?” ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, ed. James Cohen, Kara T. McAlister, Kellie Rolstad, and Jeff MacSwan, pp. 123-142. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Good, Jeff. 2017. “Threatened languages and how people relate to them: a Cameroon case study.” The Conversation <https://theconversation.com/threatened-languages-and-how-people-relate-to-them-a-cameroon-case-study-82395> accessed 23 April 2022.

Henry, Parker. 2017. “”Ewondo in the Classes, French for the Masses.” Mother-Tongue Education in Yaoundé, Cameroon.” Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2572. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2572

Mala, Nsah. 2013. Do You Know Mbesa? Yaoundé: Ansama Publications.

Moki, Edwin Kindzeka. 2020. “How Cameroon Plans to Save Disappearing Languages.” VOA News. <https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_how-cameroon-plans-save-disappearing-languages/6184626.html> accessed 23 April 2022.

Paulin, Pascale. 1995. “Etude comparative des langues du groupe Ring- langues Grassfields de l’ouest, Cameroun.” MA thesis, Université Lumière Lyon 2.

Piron, Pascale. 1997. Classification Interne du groupe Bantoïde. (LINCOM Studies in African Linguistics, 11-12.) Vol. München: LINCOM EUROPA: München: Lincom.

Yaro, Loveline. 2020. “Multilingualism as Curriculum Policy in Cameroon Education System.” Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 33(6): 26-35. DOI:10.9734/JESBS/2020/v33i630233

Kenneth Toah Nsah (whose pen name is Nsah Mala) is a poet, writer, translator, journalist and literary scholar from Mbesa in Cameroon. In March 2022, he earned a PhD in comparative literature (English and French) and environmental humanities from Aarhus University in Denmark. His doctoral dissertation was entitled “Can Literature Save the Congo Basin? Postcolonial Ecocriticism and Environmental Literary Activism.” Nsah Mala is the author and co-editor of numerous volumes of poetry and children’s books. His poems and stories also appear in many magazines and anthologies across the globe. And he has won literary prizes in Cameroon and France. Kenneth Nsah has published many peer-reviewed publications in journals such as Postcolonial Text, Orbis Litterarum, Ecozon@, and African Studies Quarterly. He has also placed journalistic articles in outlets such as Times Higher Education (UK), The Conversation (France), Corona Times (South Africa), and ERA Environnement (Comoros/France).

Thanks a million, Dr Nsah, for this article which describes the stark reality of Iteanghe Mbesa and brings it to the limelight of the whole world. May the Almighty God protect you for fighting Mbesa battles!!

Kudos sir!

This article is the best so far , thank you very much Lambert and Dr Nsah and to anyone who have contributed to realize this work.

Impressive. Kudos to Dr Nsah and all the others.

This write up is amazing!!! God bless your efforts as you continue to bring out the best of Mbessa our mother Land

I love my background Mbessa

What a beautiful and good home Mbessa

I appreciate alot for the diversity. Please what is the Mbessa’s traditional wear and can you help me with some names and their meanings, please

I love my own village Mbessa and the people of my village.

This is so great Dr. Nsah. Thanks so much for the great work.

Thanks so much Dr Nsah, for the great work, this is a very great achievement for the people of Mbessa.